![]()

Aaron Roth – Edify.org – “The Breaths We Take” – April 2013

Hi family and friends, I’ve been enjoying Lima, Peru. It’s nice to not have to repack my backpacks every three or four days. Progress with Edify has been going well; I’ve visited many schools and organizations that operate in the economically poor communities surrounding Lima.

They generally refer to the three areas of Lima: North, East, and South. I sheepishly asked, “And the West of Lima?” – “Well, that’s the ocean.” was the response. Forgive this obvious pun, but Edify is not yet interested in schools of fish. It’s nice to be at sea level though, as this newsletter will expand on. Blessings, -Aaron

- Download this email as a pdf: Aaron Roth – Apr. 2013 Update.pdf

Edify worldwide – www.Edify.org

Edify worldwide – www.Edify.org - Archive: AaronRoth.net – Monthly Newsletters

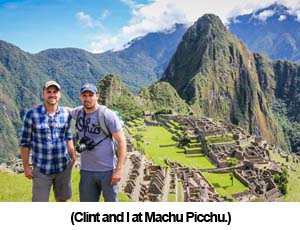

Almost two weeks ago, I went to explore a place I had only dreamed I’d be able to visit: Machu Picchu.

You can probably search the internet for a better guide and a more exciting recap of one of the seven wonders of the world, but I’ll tell you that my friend Clint Barnes, from HOPE International, and I both had the same, slightly unusual, commentary. Actually, the idea was proposed to us by a British Muslim from Liverpool, who, as he finally caught his breath at approximately 8,000 feet above sea level, told us this:

“You know it’s odd that we need a sign of humans’ remarkable innovation and ability to create advanced civilization to come and appreciate the nature of creation.”

Clint and I, both sitting down to rest our lungs, commented on how true that observation was. Machu Picchu sits on a small mountaintop in the cradle of the behemoths surrounding it, a man-made anomaly almost eclipsed by the view of towering giants. You really have to hike up a ways to see this and appreciate the true nature of its location. We started out with the intention of reaching the Machu Picchu Mountain summit, but chose to return after more than an hour of steep hiking. We had already climbed 1,500 feet in 40 min at about 5:00am earlier that morning and we needed a break.

Clint and I, both sitting down to rest our lungs, commented on how true that observation was. Machu Picchu sits on a small mountaintop in the cradle of the behemoths surrounding it, a man-made anomaly almost eclipsed by the view of towering giants. You really have to hike up a ways to see this and appreciate the true nature of its location. We started out with the intention of reaching the Machu Picchu Mountain summit, but chose to return after more than an hour of steep hiking. We had already climbed 1,500 feet in 40 min at about 5:00am earlier that morning and we needed a break.

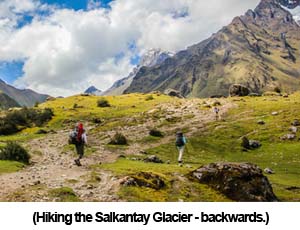

The day after, we were joined by Clint’s friend Ben, an Army doctor, and his friend Travis. We were going to attempt to do the Salkantay glacier trek, a journey of five days, in only three – and backwards. Tour operators consider it possible, but don’t advise it. If you do the regular trip forwards, you have a total elevation gain of 2,300 feet in five days, not bad to get adjusted to the altitude, but if you do it backwards, that’s an elevation gain of 8,530 feet in three days. We didn’t have porters or donkeys to carry our 40 lb packs either. Ok, yes, it was kind of ludicrous. I admit it. I’ll save the full trip summary for my blog, but suffice it to say, I have never, ever in my life struggled so hard to  breathe as I did walking up that mountain.

breathe as I did walking up that mountain.

As we approached 14,000 feet, I’d have to take a break every 10 or 15 steps to let my lungs refill and my heart to slow down. It’s basic biology: the lungs need more air and heart needs more beats to compensate for the scarcity of oxygen. By 15,000 feet, I was just ready to reach the summit and begin the descent. My head was hurting, my legs were tired, and it was hard to concentrate on anything other than breathing normally.

Clint and I, the two sea-level guys, finally made it to the summit. We rejoiced and reveled in the accomplishment and marveled at the massive blue-ish Salkantay Glacier another 1,800 feet above us. It was simply incredible. Breathtaking in both senses of the word. Soon, we descended and my lungs began to operate normally and my heart slowed down. We had achieved the seemingly impossible, overcoming mental and physical barriers to rise to the summit.

——

This past week I spent some time in the outlying districts of Lima. For the work we do in Edify, we seek out schools in impoverished areas, and provide them with small loans to build more classrooms and computer labs, and provide them Biblical business training to manage their schools more effectively. In addition to  those initiatives, we also provide teacher training so that the schools improve their level of education and stay competitive nationally. Most of these schools charge about $25-40 a month, or roughly $1-$2 a day. This may not sound like a lot to us, but this is an enormous struggle for parents. They pay it because they know the alternative is that their child will be crammed in a classroom with 35 to 40 other students. Very little attention will be paid to their son or daughter, and they probably won’t progress even in the most basic of subjects: reading and writing.

those initiatives, we also provide teacher training so that the schools improve their level of education and stay competitive nationally. Most of these schools charge about $25-40 a month, or roughly $1-$2 a day. This may not sound like a lot to us, but this is an enormous struggle for parents. They pay it because they know the alternative is that their child will be crammed in a classroom with 35 to 40 other students. Very little attention will be paid to their son or daughter, and they probably won’t progress even in the most basic of subjects: reading and writing.

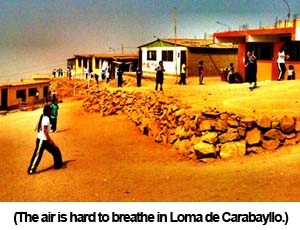

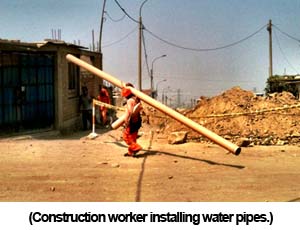

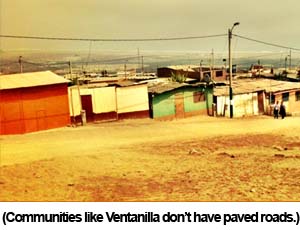

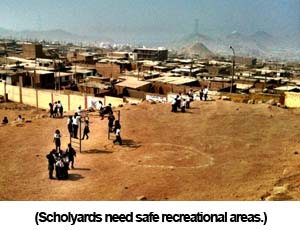

What strikes me about these districts, Callao, Ventanilla, Carabayllo is that it’s hard to breathe. Not like 15,000 feet hard to breathe, because these districts are mostly just a few hundred feet above sea level, but it’s so dusty you end up coughing a lot and worrying about what’s entering your lungs. I notice this while I’m watching students run around an unpaved recess area kicking a ball to each other. The public school director laments that with such overcrowding (more than 1 ,000) students, they’ve run out of adequate bathroom space and finances to build more bathrooms, which also means the children will wait another year or two before they can pave the recess area to deal with the tremendous amount of dirt and dust kicked up in the air.

,000) students, they’ve run out of adequate bathroom space and finances to build more bathrooms, which also means the children will wait another year or two before they can pave the recess area to deal with the tremendous amount of dirt and dust kicked up in the air.

The parents tell us that a striking number of these students have respiratory problems like asthma and other health issues caused by the poor air quality. They tell us that if they didn’t water the dirt roads in the morning you wouldn’t be able to see the houses or the schools; the dust cloud would cover the community of nearly 50,000 residents.

I think about our previous accomplishment of completing the ascent to the glacier and how hard it was for me to breathe and how proud I was that I overcame my anxieties and fears to complete the challenge. It feels a little strange to revel in the victory of the self-imposed trek in harsh air conditions, when all these children want to do run around with clean air in their lungs on a soft, safe surface like grass. They probably don’t think about it that much, but their parents, who grew up in the same community, know the long term dangers of consistent exposure. They mention health problems like the kind that miners in coal towns can develop.

What comes next for me, and for this newsletter to you all is just a question: “What is our response?”

I don’t believe we should feel guilty for taking trips to Machu Picchu or the Salkantay Glacier (forwards or backwards) or putting ourselves in conditions where we must push ourselves to overcome our limits. No, I believe the response is to carry out the words we use to describe our identity. When we say we are the kind of people who care about making a difference in the world, who care about being light and salt of the Earth, who care about those without hope or a future, who care about sharing the hope of Christ here and now, and in heaven – we must do the simple things to follow through.

It means that for the thousands of school aged students in places like Loma de Carabayllo, we must find ways of providing better education and a more healthy educational experience. In short, it means being involved in local government, paving roads, providing loans to build better recess areas, and educating children and parents the importance of health in the young body.

I thought about this on the long bus ride back, about the dust, and the wind, and the breaths we take. It made me think about these verses in the Bible:

Then the LORD God formed the man from the dust of the ground. He breathed the breath of life into the man’s nostrils, and the man became a living person. (NLT Genesis 2:7)

The Spirit gives life; the flesh counts for nothing. The words I have spoken to you—they are full of the Spirit and life. (NIV John 6:63)

I pray that we are being filled will the breathe of life, and with the breaths we take we can share words of the Spirit and life.

Blessings to you and your family,

-Aaron