In Nicaragua, getting out of bed on Thursday morning was difficult. Everyday, we awoke to sore muscles, but this day I knew we were going to visit La Chureca, the enormous dump in Nicaragua. Emotionally, I didn’t feel ready to visit the dump. I was not looking forward to what I was going to see. I don’t know if it was the impending guilt or shame for living such a comfortable lifestyle, knowing that the people I was to meet had next to nothing, or that I was probably going to see something that would shake me up inside.

Riding in the back of a pickup into La Chureca my nostrils were assaulted by the foul smells. It was probably the worst smell I’ve ever experienced. Food scraps, soiled clothes, and used toilet paper (since no one is allowed to put used toilet paper down the toilet) get thrown away and everything gets hauled to the dump. Consequently, when the trash workers are burning the heap, you smell everything undesirable. It was extremely hot and humid that day, so I also smelled rotten food and other sun-baked refuse. Birds circled over the heads of the trash workers who wore long pants and shirts and rubber boots. They carried with them long poles that looked like forks and they looked for items of value: clothes, plastics, glass, metals, anything that could be sold or used for their dwellings. People can make a living at the dump, and have been doing so for quite some time.

La Chureca began almost 40 years ago after a hurricane destroyed the homesteads of Nicaraguans. Families began to move into the area because they were able to earn a living picking saleable things from the trash. The government gave some subsidies for housing with the perspective that it was all temporary community – these people would leave as soon as conditions improved. Today there are more than 500 families living at the dump. Families are large at the dump, so 500 families can mean anywhere from 2,000 to 3,000 people.

A beacon of hope in the area is the local church run by Pastors Ramon and Miriam Baca. Inititally they had it inside the walls of the dump so that it was close to the people living in the community. Recently, they changed the location of the church to outside the dump so that all churchgoers would feel the literal and figurative sense of life beyond the walls of the mountains of trash. We participated in the daily feeding station that the local church operated.

After a short tour of the area, I think most of our group was exhausted from the shock of viewing the living conditions. For me, I know I have never been in a place this bad. I almost feel shame for saying that because what happened next shocked me more than the unsanitary abodes we toured.

About 50 children sat in colored plastic chairs to wait patiently for lunch. They were all smiling and playing with each other. Brothers, sisters, cousins, and friends – these kids were part of a tight-knit community in La Chureca. Despite not having shoes, or clean hands or faces, these kids were still kids.

They took joy in poking each other, putting their arms around the shoulders of a friend, and greeting all the Americans with waves and hugs. I thought to myself, “How can such beauty and warmth exist in such a terrible place?”

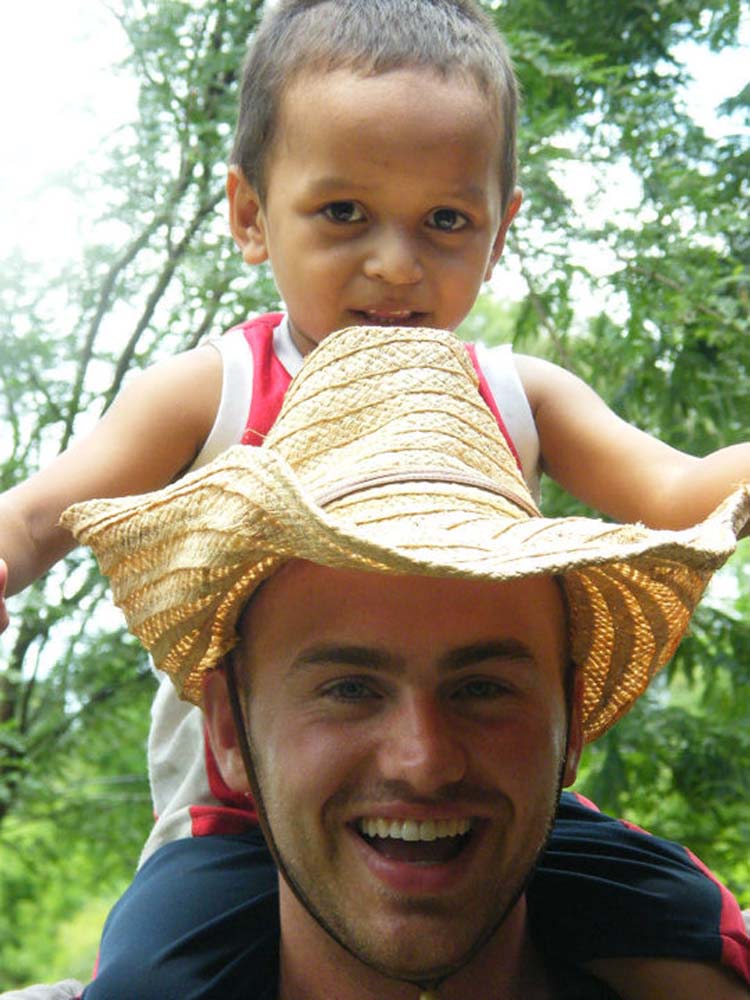

As I was trying to process this in my mind, a little guy turned around and started talking to me. I learned that his name was Pancho. Pancho didn’t have a plate with him so I asked him if he wanted to eat. He said that he had already eaten and all he wanted was for me to put him on my shoulders. He walked out from the area of chairs and motioned for me to crouch down. He walked around to my back and began to climb up to my shoulders. I was thinking to myself that those little barefeet were incredibly dirty. I probably had little footprints on my back.

Pancho started to say “Caballo, Caballo!” which means “horse” in Spanish. So I galloped around the yard with Pancho the cowboy – the Caballero – on my shoulders. He was squealing with laughter. I was smiling too. I knew that there is not much I could do for him at that moment except to show him love and kindness.

As I was galloping around, Pancho was saying something to me that I had to stop and listen for him to repeat again. “Como?” I asked.

Pancho said (translated):

“Let’s go to my house.”

“Where is your house?”

“Over there, just up the street.”

“You live close to here?”

“Yes, lets go to my house and say hi to mama . . .”

Whew.

At that moment I got a big lump in my throat. I felt as though time stopped and everything about this dump, all my perceptions came crashing down. Pancho, the little caballero, did what anyone does when playing with new friends – he invited me to his house to say hi to his mama. I imagined what his house might look like . . . the dirt floors, the rusted metal sheets pieced together to form a wall, broken furniture, holes in the roof, and a makeshift table where he and his brothers and sisters would eat what little food his mother prepared.

I wanted to cry.

How could this little boy with dirty feet, dirty hands, and a dirty face, wearing a shirt that was so old the printed graphic had faded away, be so kind, so full of joy, so much like every other child in America?

See, the most shocking thing for me that day was not that La Chuleca was so dirty and desolate, it’s that there was a such a bright spirit of happiness in those kids, in that community, and in my friend Pancho.

I had to put Pancho down because we were leaving. He said to me that he wanted to ride on my shoulders again. I said, “I’m sorry Pancho. I have to leave.” He said, “Ok.” And then he said something that I couldn’t understand. I wished that I knew what he meant. As I jumped back on the pickup to leave, Pancho came to the edge of the feeding area and waved and said it again. I still didn’t know what it meant, but my guess is that it was an invitation to come back and play, because I still needed to meet his mama . . .